Germany is known for its half-timber medieval buildings, and many towns proudly promote these charming structures. But to my delight, each has also had a buried past. The cities are much older than they seem. In some areas, especially the south, you often find Roman ruins beneath them. And in Bavaria, in particular, there is most likely evidence of the Celts beneath those. I love peeling back the layers.

Germany is known for its half-timber medieval buildings, and many towns proudly promote these charming structures. But to my delight, each has also had a buried past. The cities are much older than they seem. In some areas, especially the south, you often find Roman ruins beneath them. And in Bavaria, in particular, there is most likely evidence of the Celts beneath those. I love peeling back the layers.

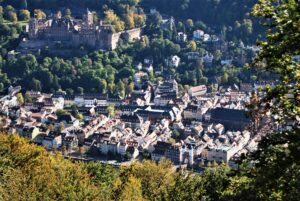

I’d heard so much about Heidelberg that when we had a three-day weekend, I suggested we check it out. We enjoyed it very much, staying on the edge of the Altstadt (old town) and exploring the old city. The castle was first mentioned in 1225 and was modified over different periods, reaching its heyday in the Renaissance.

The current Old Stone Bridge dates to 1788, which is relatively young by comparison. It is the ninth bridge to span the Neckar River, each of its predecessors destroyed by ice floes. The earliest known bridge was constructed of wood by the Romans in the first century AD. During work on the current bridge, a wooden timber was discovered from the original. It was later carbon-dated to the time of the Romans, matching the records they left behind. The Romans’ next bridge of stone was also destroyed by ice.

The current Old Stone Bridge dates to 1788, which is relatively young by comparison. It is the ninth bridge to span the Neckar River, each of its predecessors destroyed by ice floes. The earliest known bridge was constructed of wood by the Romans in the first century AD. During work on the current bridge, a wooden timber was discovered from the original. It was later carbon-dated to the time of the Romans, matching the records they left behind. The Romans’ next bridge of stone was also destroyed by ice.

The university here is the oldest in Germany, opening on 13 October 1386. As I write this on 13 October, it is celebrating its 686th birthday! It even has a student prison for crimes such as delinquency, brawling, or disturbing the peace.

But the hill opposite drew my eye. The two-kilometer Philosopher’s Way is about 200 meters above the river. Walking along it, you can get a good sense of how the city grew over time, with the castle looming above, looking down on the town. It is easy to see the narrow alleyways of the oldest portion meandering off the central Platz. These became wider and more regular as the city grew.

But the hill opposite drew my eye. The two-kilometer Philosopher’s Way is about 200 meters above the river. Walking along it, you can get a good sense of how the city grew over time, with the castle looming above, looking down on the town. It is easy to see the narrow alleyways of the oldest portion meandering off the central Platz. These became wider and more regular as the city grew.

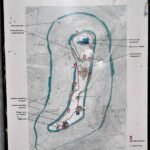

Known as Heiligenberg, or Holy Hill in German, the tree-covered sandstone mountain doesn’t look like much when viewed from modern Heidelberg. But its history dates back to 5,000 BC after archaeologists found Neolithic pottery on the summit.

As you near the top, approximately 440 meters (1445 feet) up, the first site you see is the Nazi amphitheatre established in 1934 on top of the older ruins. This is an open-air theatre built for the Third Reich. It seats 8,000 with standing room for an additional 5,000. On its unveiling, Joseph Goebbels compared the holy hill to “National Socialism in stone.”

The 11th-century monastery of St Stephen lies on the lower summit. The stones of this were robbed from the grounds in the 19th century when the adjacent Heiligenberg Tower was built. Widgit studied the walls.

The monastery of St Michael was begun on the upper summit in 1023. Though as early as 870, a small church was constructed by Lorsch Abbey on top of a Roman temple. Occupied by several religious orders, it was abandoned by the 1700s.

During Roman occupation, a temple to Mercury was built on the top, the apse of which can still be seen inside the abbey church. The discovery of votive stones, with the inscription Mercurius Cimbrianus, suggests a place of worship. The site was plundered during the migrations after the fall of Rome. But burials continued as late as the year 600.

And further back in time, surrounding it all, is the double-walled hill fort of the early Celts. Dating to the 5th century BCE, the walls encompass the upper and lower peaks. During the La Tène period of the late Iron Age, they were mining iron ore on the site. Until the 2nd century BCE, this was a thriving political, cultural, and religious center.

Peeling back the layers of time is one of my favorite things to do. And this portion of Europe affords ample opportunity. It seems everywhere we go, we find medieval life on top of Roman civilization with iron age Celtic history underneath it all.