Today is Father’s Day, and Dave’s gift will be the same thing he got for Christmas: a ride on a steam train. He loves trains, and this time, I chose a different route. For the previous trip, we had a lovely ride through the mountains of western North Carolina on the Great Smoky Mountain Railroad. The train departed from Bryson City and had a layover in Dillsboro, a quaint town with lots of shops, before returning to Bryson City. The track follows the scenic Tuckasegee River and passes through the 836-foot-long Cowee Tunnel.

Today is Father’s Day, and Dave’s gift will be the same thing he got for Christmas: a ride on a steam train. He loves trains, and this time, I chose a different route. For the previous trip, we had a lovely ride through the mountains of western North Carolina on the Great Smoky Mountain Railroad. The train departed from Bryson City and had a layover in Dillsboro, a quaint town with lots of shops, before returning to Bryson City. The track follows the scenic Tuckasegee River and passes through the 836-foot-long Cowee Tunnel.

I’m looking forward to riding the Allegany Special through the Shenandoah Valley later this week.

As you know, I am typically interested in older history. Still, I find myself drawn to elements of the modern industrial age, and trains played a major role in those advancements. The history of steam trains is a fascinating journey involving technological innovation, industrial growth, and significant societal change. Prior to the age of steam, horses pulled wagons along wooden or metal rails. New inventions created the opportunity for a new method of transport, and the steam engine soon replaced horse or mule power.

In 1712, Thomas Newcomen invented a steam-powered engine to pump water from mines by combining the ideas of Thomas Savery and Denis Papin. Newcomen replaced the vessel where the water condensation occurred with a cylinder containing a piston. Instead of the vacuum drawing in water, it drew down the piston. Newcomen’s design was an improved method for miners who needed to lift water out of tin mines.

In 1712, Thomas Newcomen invented a steam-powered engine to pump water from mines by combining the ideas of Thomas Savery and Denis Papin. Newcomen replaced the vessel where the water condensation occurred with a cylinder containing a piston. Instead of the vacuum drawing in water, it drew down the piston. Newcomen’s design was an improved method for miners who needed to lift water out of tin mines.

Later, James Watt took this a step further. While repairing a steam engine in 1764, Watt noticed the incredible amount of wasted steam. He wrestled with the problem and, in 1765, came up with an idea for a separate condenser. Watt realized the loss of heat was the primary defect in the original engine and devised a separate chamber from the cylinder to create condensation, thus improving the efficiency of the steam engine and making it more practical for other uses. This idea had an enormous impact on industrial society. For the first time, reliable and efficient motive power was available.

noticed the incredible amount of wasted steam. He wrestled with the problem and, in 1765, came up with an idea for a separate condenser. Watt realized the loss of heat was the primary defect in the original engine and devised a separate chamber from the cylinder to create condensation, thus improving the efficiency of the steam engine and making it more practical for other uses. This idea had an enormous impact on industrial society. For the first time, reliable and efficient motive power was available.

Early prototypes included one by Richard Trevithick, who, in 1804, built a full-scale steam-powered railway locomotive. It could haul heavy loads and ran on a track in South Wales. His locomotive proved the theory that steam-powered rail transport was possible.

In 1812, Matthew Murray built the Salamanca, the first commercially successful steam locomotive. Salamanca, named after the Duke of Wellington’s victory earlier that year, ran on the Middleton Railway through Leeds, England, 17 years ahead of Stephenson’s Rocket. Murray’s design was the first to incorporate two cylinders.

In 1812, Matthew Murray built the Salamanca, the first commercially successful steam locomotive. Salamanca, named after the Duke of Wellington’s victory earlier that year, ran on the Middleton Railway through Leeds, England, 17 years ahead of Stephenson’s Rocket. Murray’s design was the first to incorporate two cylinders.

However, George Stephenson is recognized as the “Father of Railway”. His famous “Locomotion No. 1” was the world’s first public railway. This steam locomotive hauled passengers between Stockton and Darlington in 1825. In 1830, Stephenson built the first public inter-city rail line, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. This was the first fully operational railway line run only on steam power. George and his son, Robert, also built the famous “Rocket” locomotive, which won the Rainhill Trials in 1829 and displayed its superior design.

Stephenson also created a standard gauge for the rails of 1435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in), enabling trains to move about from place to place on compatible tracks. Most countries adopted the Stephenson Gauge. However, as Dave and I found out, Warsaw Pact nations, such as the Czech Republic, had their own system. And people must change trains at the border.

During the mid-19th century, the UK experienced rapid growth and investment in railways, leading to the construction of extensive rail networks.

And the technology spread. The steam locomotive arrived in the United States in the early 19th century. In 1827, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was among the first to build and operate steam-powered locomotives. The First Transcontinental Railroad, completed in 1869, significantly boosted westward expansion.

And the technology spread. The steam locomotive arrived in the United States in the early 19th century. In 1827, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was among the first to build and operate steam-powered locomotives. The First Transcontinental Railroad, completed in 1869, significantly boosted westward expansion.

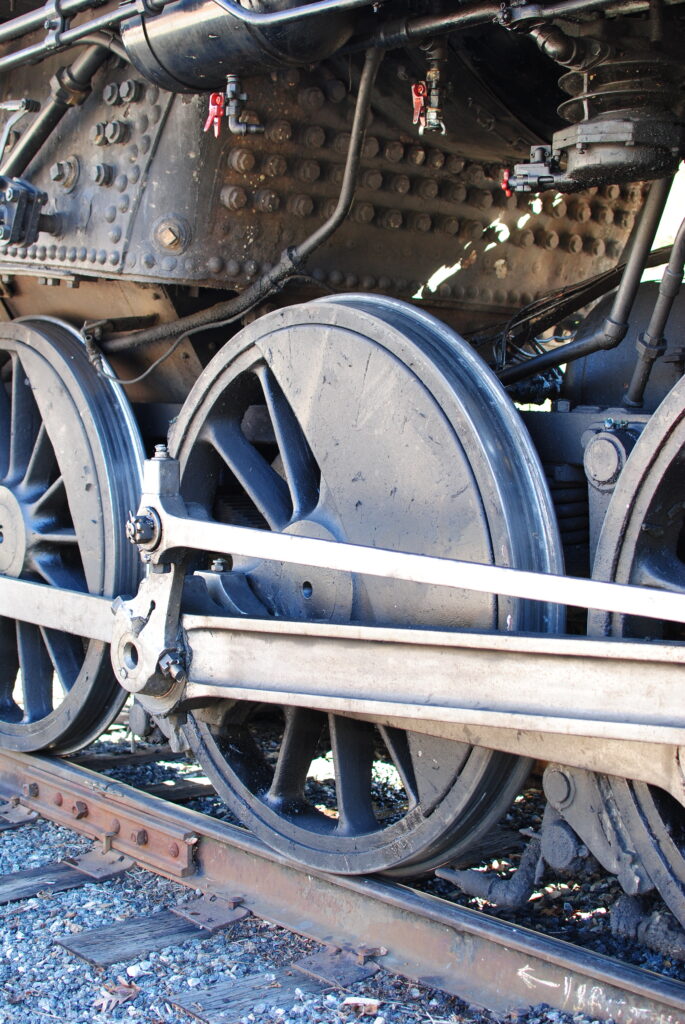

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, steam locomotives grew more powerful and efficient. Innovations included compound engines, super-heating, and improvements in boiler design. Famous steam locomotives include the “Flying Scotsman” and the “Mallard,” which set the world speed record for steam locomotives at 126 mph in 1938.

While the steam engine was initially designed to help miners, it was soon the preferred method for moving goods and people, bringing about profound change. Trains enabled the fast and efficient transport of raw materials to factories and finished products to a broader range of markets. They provided access to remote areas for natural resources like timber and coal. Farmers could transport produce quickly and with little spoilage.

and people, bringing about profound change. Trains enabled the fast and efficient transport of raw materials to factories and finished products to a broader range of markets. They provided access to remote areas for natural resources like timber and coal. Farmers could transport produce quickly and with little spoilage.

Building railways created many new jobs, from construction workers to engineers. Operating and maintaining the railway network required a workforce in various roles, such as conductors, stationmasters, and maintenance crews.

Railways made commuting feasible. People could live farther from where they worked, leading to urban sprawl. New towns and cities sprang up around railway stations and junctions, often becoming critical economic centers. The town we recently moved to is an old railroad town, and while the train no longer stops here, I frequently hear the whistle as it passes through town.

Trains made long-distance travel easier and more affordable for ordinary people, facilitating leisure travel, migration, and cultural exchange. While we lived in Europe, Dave and I often traveled by train.

Trains made long-distance travel easier and more affordable for ordinary people, facilitating leisure travel, migration, and cultural exchange. While we lived in Europe, Dave and I often traveled by train.

Railways facilitated the distribution of newspapers, mail, and other services, enhancing communication and access to information.

Of course, technology has a downside. Railway construction often caused significant changes to landscapes, deforestation, and ecosystem disruption. Locomotives powered by coal contributed to air pollution. The construction of the tracks occasionally led to the displacement of communities and indigenous peoples.

While high-speed trains are now available at speeds of 200 miles per hour, I enjoy the romanticism of the old steam trains. I look forward to our ride through the Shenandoah later this week.

Do you ever take the train?