I’m wrapping up Native American Heritage Month with a visit to Wolf Creek, a reconstructed Native site about a half hour away. We’d passed highway signs for it before, but we were always on our way somewhere else. So, despite a bit of snow on the ground, we trudged down the hill to visit the village.

In the 1930s, a farmer found arrow points and bits of pottery in one of his fields. It wasn’t much, but since he hadn’t found any in his other fields, he wondered if that plot of land was something special. When he discovered a skeleton, he called in a local historian who agreed that it was old. The two men covered the site and marked it as a grave, but the farmer never plowed that field again.

Fast forward to 1970, when the construction of Interstate 77 began, and plans were made for an off-ramp at Bastian, Virginia. This effort would require Wolf Creek to be rerouted. Wayne Richardson, a resident, contacted State Archaeologist Howard MacCord, informing him of the possible existence of an Indian village on the site, which would be disturbed if the project continued.

Construction was halted, and MacCord was given 30 days to perform a rescue operation to save what he could. This project was the first official state-recognized archaeology site in Bland County (#44BD1). To expedite the mission, road graders (or the JCB for you Time Team fans) were brought in to remove the topsoil, which severely damaged the upper layers of the site. Working around the clock, including through the night by using the headlights of cars, MacCord and his team set out to save what they could.

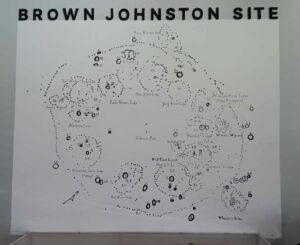

Since there were numerous arrow points, pottery sherds, and other daily items, they collected a sampling of those and focused instead on the graves, post holes and post stains for the structures and the palisade, storage huts, and firepits. Doing this allowed them to create a pole for pole and feature for feature map identifying structures and firepits. Named the Brown Johnston Site after the farmer who owned the land, the village was reconstructed 200 feet from the original site between 1992 and 1996 using MacCord’s maps to make it as authentic as possible.

The main features include 229 post molds of the palisade fence that surrounds the village. It was not a defensive structure but rather a protection from weather and likely would have consisted of interwoven vines and branches. MacCord also identified post molds in a circular pattern for 11 houses and at least one square storage hut. The structures varied in size and may have held 6-16 people in each. The largest structure was located inside the s-shaped entrance and may have been a gathering place.

Fourteen skeletal graves were found, all but one buried within the palisade wall. They varied in age and gender, and a few contained personal items made of bone and shells. It was interesting how the burial methods varied. Some were described as loosely arranged, whereas others were tucked tightly. The directions in which they were laid also varied greatly. Great care has been taken to place these precisely as they were found on the original site.

Debris in the firepits consisted of burnt kernels of corn and the bones of numerous animals, including deer, elk, and squirrel. Tools made of bone, shell, and stone were found, and from those, they determined they were primarily an agricultural society. Based on the corn discovered in the firepits, they likely grew the three sisters: corn, beans, and squash. Arrow and spear points, along with scraping tools, provide evidence of hunting. Our guide said she had been told there was a type of bison in the area, but she told us nothing more significant than small bears had been found. Living on the creek would have provided fish for their diet as well.

Carbon dating places the site between 1480 and 1520 AD, and, likely, it was only occupied for about ten years. And while the excavation was done quickly, MacCord believed the people had packed up and moved on as the quantity of tools and other items was not as great as he suspected if they had been run off of their land and left their belongings behind.

The homes were reconstructed using bamboo to mimic the river cane that was prevalent in the area at the time. Most likely, the bark used back then would have been American Chestnut, which was readily available. However, chestnuts were wiped out in the early portion of the 20th century. It is theorized that the homes would have been covered in mud during the winter months for insulation.

The lack of time for an in-depth study and the migratory nature of the people do not allow us to pinpoint the exact tribal affiliation of those who lived here. Still, the time frame and the items found indicate they were part of the Late Woodland Native (900-1600 AD) culture. As this part of Virginia formed a crossroads, they may have spoken an Algonquian, Siouan, or Iroquoian language. They lived in circular houses, practiced agriculture, hunted, and fished. They made tools from available materials. Daily tasks were divided among the community members, who probably lived in kinship groupings. Based on the discovery of a number of exotic items, such as mica, beads, copper, and shells, they must have been part of the extensive trade routes that interlaced the area.

While much of Wolf Creek remains a mystery, we get a glimpse into their life. The recreated village is a unique resource to preserve and educate the public about the rich history of these indigenous people, how they lived, how they adapted to their environment, and how they interacted with neighboring societies. Through the efforts of the museum, we can learn about life in North America prior to European Contact.

Very interesting and well written. Thanks for sharing.