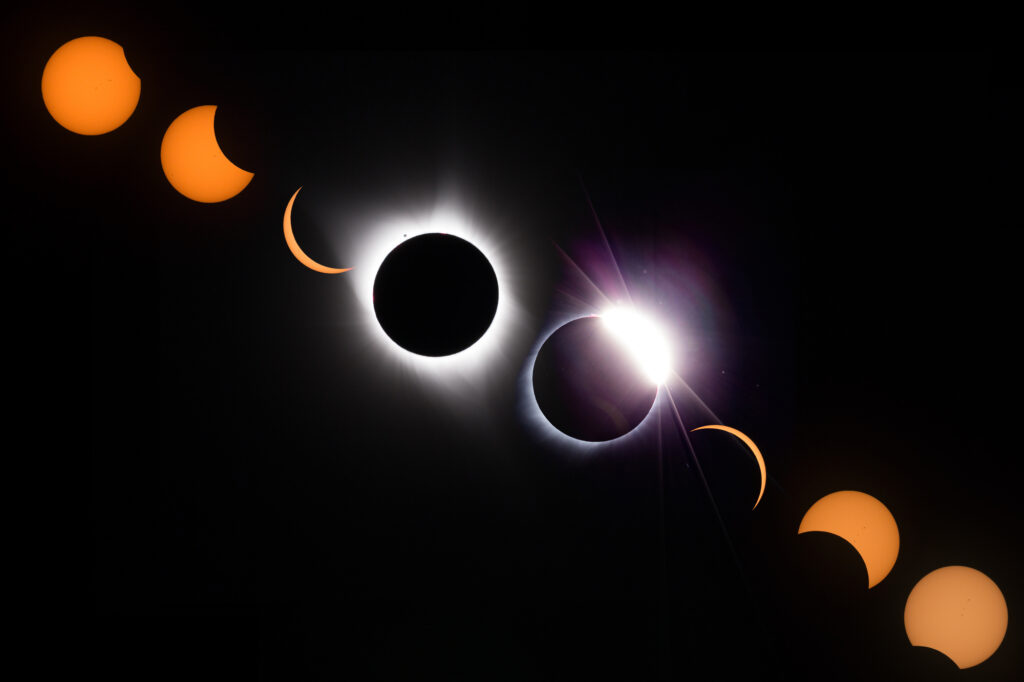

This past week, a large swath of the U.S. saw a total eclipse. While it was tempting to go, the timing just wasn’t right for us to travel. I watched the near-total eclipse from the NASA Space Center at Wallops Island in August 2017. Though we were at 82% coverage, I remember the dimness as I sat with others along the shoreline. It felt so eerie, a green tinge to the air. With our special glasses, we watched the moon pass in front of the sun and oohed and aahed at the sight.

This past week, a large swath of the U.S. saw a total eclipse. While it was tempting to go, the timing just wasn’t right for us to travel. I watched the near-total eclipse from the NASA Space Center at Wallops Island in August 2017. Though we were at 82% coverage, I remember the dimness as I sat with others along the shoreline. It felt so eerie, a green tinge to the air. With our special glasses, we watched the moon pass in front of the sun and oohed and aahed at the sight.

So, this week, with a predicted 87% coverage, I didn’t mind staying home to watch. I know nothing beats being in the path of totality, but I remembered the sensations from seven years ago and expected more. Maybe I expected too much, but this year seemed to be less dim, less otherworldly than the one in 2017. Perhaps I should have traveled.

I went outside to watch from our porch swing on a beautiful, cloudless spring day. Just before the moon began its journey, I snapped a shot of the shadows on the sidewalk in front of me. They were crisp and sharp. We had just returned home the day before, and I had not planned ahead and gotten eclipse glasses. So I knew I could not watch the transit and tried to capture it by punching a hole in a piece of cardboard with limited success. Instead, I paid attention to the world around me. I watched several species of birds flying  around. Robins, Cardinals, and Grackles. The trees were alive with chirping birds. Bees buzzed in the flowers below me and on the dandelions I’d asked Dave not to mow yet.

around. Robins, Cardinals, and Grackles. The trees were alive with chirping birds. Bees buzzed in the flowers below me and on the dandelions I’d asked Dave not to mow yet.

With the research I’d done lately on ancient peoples, I was curious how they reacted to such phenomena. Each culture’s reaction reflected their relationship between celestial events and their natural world. There seem to be two primary theories. The first is that the sun is being attacked. In ancient China, they believed a mighty celestial dragon devoured the sun. The Incas thought a jaguar was attacking the sun. Koreans believed mythical creatures were trying to steal the sun away. One I found particularly interesting was the Cherokee, who thought a giant frog was attempting to eat the sun.

They reacted by dancing around, banging on drums, and making other loud noises to scare away the threat. Others, such as the Mayans and Koreans, fired arrows at the sky to chase away the demons.

The second group viewed this event as a warning from the gods of upcoming disasters or change. Many Europeans saw this as a bad omen, possibly signifying the forthcoming death of a leader. The Navajo Nation in North America believed it was a time when the sun  and moon were in conflict. The ancient Celts viewed the eclipse as a battle between light and dark forces.

and moon were in conflict. The ancient Celts viewed the eclipse as a battle between light and dark forces.

For the Navajo, this was a time to join together to resolve their conflicts within themselves and with others to restore the balance. Several tribes believed humans needed to intervene with songs and ceremonies to bring all things back into alignment and restore harmony. Celtic Druids led their people in rituals designed to appease the gods and restore the natural order. Other cultures saw it as a time for reflection and renewal.

The Greeks, however, were the first to get it right. Aristotle described the Earth as a sphere, and the darkening of the sky was caused by the moon passing between the Earth and the sun. The Romans, who were heavily influenced by the Greeks, picked up on this, and later, Ptolemy took the theory further, though his models were still based on an earth-centric cosmology.

I mulled all this over as I sat on the porch. Our older cats and the dog were snug inside and slept through the entire event, so I cannot report on their reactions. However, as the sky dimmed, and the breeze died down, the bees disappeared. And soon, I noticed the birds were no longer flitting about or chirping in the trees. There was silence in the neighborhood. I rose from my seat and took a photo of the shadows on the sidewalk, their edges indistinct, softened by the weak sunshine filtering through the trees.

Maybe next time, if I am still around and able to travel, I will go to the path of totality. Or perhaps I will travel to another part of the world. After all, there are 2-5 eclipses per year falling somewhere on the Earth, with a total eclipse occurring about every 18 months.

Maybe next time, if I am still around and able to travel, I will go to the path of totality. Or perhaps I will travel to another part of the world. After all, there are 2-5 eclipses per year falling somewhere on the Earth, with a total eclipse occurring about every 18 months.

Did you view the eclipse this year? What were your impressions?