For my birthday this year, Dave bought a ticket for me to visit the Monet Experience in the District. I’d thoroughly enjoyed the Van Gogh Experience in Munich the year before. However, I prefer Monet’s works and was excited to go.

For my birthday this year, Dave bought a ticket for me to visit the Monet Experience in the District. I’d thoroughly enjoyed the Van Gogh Experience in Munich the year before. However, I prefer Monet’s works and was excited to go.

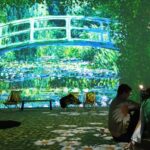

Everyone has their personal preferences in terms of art, and Dave is not a fan of the Impressionists. I, on the other hand, love their use of light and color, eliciting an emotional response to their view of everyday scenes. I’d visited Giverny, his home, and wandered with my parents through the gardens Monet painted. A small copy of the Japanese bridge in his garden at Giverny hangs in my living room. So it was the perfect birthday gift.

After spending time in the first few rooms, which provided insight into his life and the Impressionist movements, I dawdled in the room filled with furnishings and moments from his life, including quotes. “Every day, I discover even more beautiful things. It is intoxicating to me, and I want to paint it all-my head is bursting.”

In the main room, I settled on a cushion in the middle of the floor and let the light and colors wash over me as the room filled with his paintings, the colors, and even the brush strokes.

Oscar-Claude Monet was born on 14 November 1840 in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, the second son of Adolphe and Louise Justine Monet. By 1845, the family relocated to Le Havre in Normandy. As a child, he loved to draw, and his mother, a singer, encouraged him. His father, however, had plans for him to join the family’s ship-chandling and grocery business. Despite his father’s wishes, young Oscar entered the Le Havre secondary school for arts in 1851. By the age of 15, he was drawing caricatures of acquaintances for money.

Oscar-Claude Monet was born on 14 November 1840 in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, the second son of Adolphe and Louise Justine Monet. By 1845, the family relocated to Le Havre in Normandy. As a child, he loved to draw, and his mother, a singer, encouraged him. His father, however, had plans for him to join the family’s ship-chandling and grocery business. Despite his father’s wishes, young Oscar entered the Le Havre secondary school for arts in 1851. By the age of 15, he was drawing caricatures of acquaintances for money.

When his mother died in 1857, Monet went to live with his aunt, Marie-Jeanne Lecadre, who willingly financed his education. From 1858 to 1860, he continued his studies at the Academie Suisse in Paris, where he met Camille Pissarro. It was around this time he studied with Eugene Boudin, who encouraged him to develop his skills in the “en plein air” style of painting, which involved completing the entire project outdoors rather than doing sketches and painting inside a studio later.

When he was called up for military duty, he was sent to Algeria, which had a powerful effect on the young man who often spoke of the impact of the light and colors there. On his return, he studied at Charles Gleyre’s studio, where he met Renoir and Bazille, who became his closest friends. They traveled to Honfleur, where they were joined by Alfred Sisley, who shared his desire to show the beauty of conventional subjects.

During the Franco-Prussian War, he spent time in the Netherlands and London, most likely to avoid being called up again. While in the Netherlands, he was influenced by Dutch painters, and when he moved to London, he acquired a sailboat to apply those techniques to painting the Thames. When the family moved to Argentueil in 1871, they lived in the “rose-colored house with green shutters,” where Monet produced fifteen paintings of his garden, which was the single most important motif of his time there. This concept of painting the same subject in a series of different times of day and different seasons became a trademark of his works.

During the Franco-Prussian War, he spent time in the Netherlands and London, most likely to avoid being called up again. While in the Netherlands, he was influenced by Dutch painters, and when he moved to London, he acquired a sailboat to apply those techniques to painting the Thames. When the family moved to Argentueil in 1871, they lived in the “rose-colored house with green shutters,” where Monet produced fifteen paintings of his garden, which was the single most important motif of his time there. This concept of painting the same subject in a series of different times of day and different seasons became a trademark of his works.

In his early career, Monet, like the other impressionists, was out of favor with The Salon, the traditional painters, and was rarely accepted into juried events. Monet was often in financial difficulties. It wasn’t until this band of radical artists went out on their own and drew public acclaim that the movement took off, and these unconventional painters gained acceptance.

accepted into juried events. Monet was often in financial difficulties. It wasn’t until this band of radical artists went out on their own and drew public acclaim that the movement took off, and these unconventional painters gained acceptance.

So, what is Impressionism? The name comes from a negative review from art critic Louis Leroy, who commented that Monet’s Impression: Sunrise was unfinished. Soon, however, more progressive critics hailed the work as a depiction of modern life.

While none of the characteristics of the style were new, the Impressionists were the first to put the techniques together and use them consistently. These paintings consisted of short, thick strokes that quickly captured the essence of the subject instead of intricate detailing. Using a knife to smear thick layers, a process known as impasto, often leaves the stoke marks behind. Colors are applied side by side with as little mixing as possible to create movement to the eye. Red and blue next to each other shows as purple. This process makes the color appear more vivid.

Other techniques include the avoidance of black, instead using grays and dark tones to produce complementary colors. The paint is applied to a light-colored ground, often light gray or beige. Light is essential. As mentioned before, painting was done en plein air, outdoors, where the light played a significant role in the final product. Bold shadows give a sense of freshness, which was inspired by noticing the blue shadows in the snow.

During this time, synthetic pigments in tubes became readily available, and artists no longer had to grind and mix their own colors. New colors appeared, such as cobalt blue, viridian, cadmium yellow, and ultramarine blue, and were in use by the mid-19th century.

Over time, these artists earned their place among the greats in the art world.

Over time, these artists earned their place among the greats in the art world.

Some of you may be wondering about the title of this article: See Like a Bee. It has often been said Claude Monet saw like a bee. People see colors differently, but some have a better eye than others. Paul Cézanne once said, “Monet is only an eye—but my god, what an eye.”

In the early 20th century, Monet developed cataracts and was slowly losing his vision. He confided in friends that he was terrified of going blind and not being able to paint. Cataract surgery was new and came with high risks. His friend and fellow painter, Mary Cassatt, went blind after two surgeries to correct her cataracts. So, it’s no wonder he was hesitant to undergo the surgery.

He finally succumbed and agreed to have the procedure done, and it was a success. In fact, it was so successful that according to scientists studying his later works, his ability to see color sharpened following the surgery, possibly into the realm of the ultraviolet. I won’t bore you with the science, but humans have three types of cones, allowing us to see a broader range than most animals, which have only two. Dogs, for example, cannot see red. It doesn’t appear as vibrant as it does to humans.

He finally succumbed and agreed to have the procedure done, and it was a success. In fact, it was so successful that according to scientists studying his later works, his ability to see color sharpened following the surgery, possibly into the realm of the ultraviolet. I won’t bore you with the science, but humans have three types of cones, allowing us to see a broader range than most animals, which have only two. Dogs, for example, cannot see red. It doesn’t appear as vibrant as it does to humans.

Insects, on the other hand, see the shorter wavelength of ultraviolet rays. For many, their survival depends on identifying specific species of flowers. Some have ultraviolet patterns that attract bees. Humans cannot see these, which some scientists refer to as “bee purple.” Certain butterflies have ultraviolet colors on their wings to distinguish males from females.

So, I’m not suggesting you run out and have cataract surgery, but I have to wonder if this is true. All of that science aside, I do love Monet’s work, and if you are interested, here is a list of what many consider his best works.

Do you enjoy the impressionists?

Impression, Sunrise 1872

La Grenouillère, 1869 (visited with Renoir)

Rouen Cathedral, Façade

Woman with a Parasol, 1875

Houses of Parliament, 1901-1902

San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk 1908

Nymphéas (Waterlilies) Spent 30 years painting over 250 canvases of waterlilies

Haystack at the End of Summer 1890-1891 (series)

Japanese Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies (series)

The Saint-Lazare Station (series)

The Beach at Sainte-Adresse (series)

The Artist’s Garden at Giverny (series