What springs to mind when someone uses the term ghost ship? Are you like me and envision the Black Pearl from the Pirates of the Caribbean movies? When I heard there was a ghost fleet in nearby Mallows Bay, I was intrigued. They offer kayak tours, so of course, I signed us up.

What springs to mind when someone uses the term ghost ship? Are you like me and envision the Black Pearl from the Pirates of the Caribbean movies? When I heard there was a ghost fleet in nearby Mallows Bay, I was intrigued. They offer kayak tours, so of course, I signed us up.

Mallows Bay, located on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, is known for having the largest ship graveyard in the Western Hemisphere. Not only has it been named a National Marine Sanctuary, but the Bay is home to over 230 shipwrecks, of which 108 date back to the shipbuilding boom in World War I.

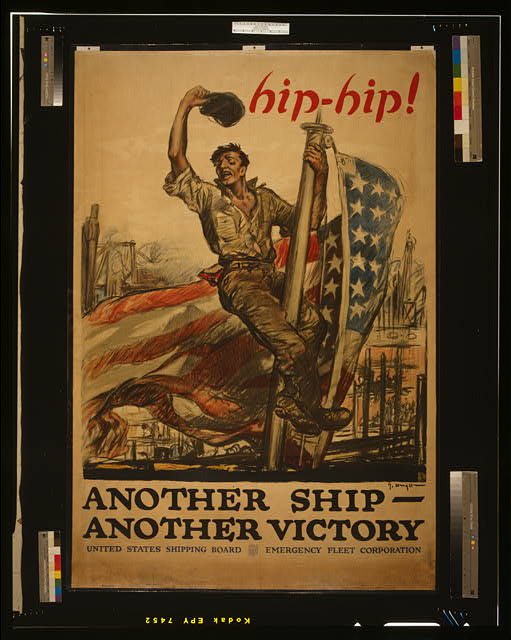

Prior to World War I, the U.S. was second only to Great Britain in shipbuilding. When the U.S. entered the war in April 1917, the Woodrow Wilson administration jumped into action, implementing a shipbuilding campaign organized by the newly formed Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) to relieve the depleted merchant fleet destroyed by German U-boats. With estimates that the war would last for several years, the EFC unveiled an ambitious program to build an initial 1,000 ships from steel, wood, and even concrete. The EFC was the forerunner of today’s Merchant Marine.

While many believed the days of wooden ships were numbered, it was decided that by using wood, ships could be built faster using the U.S.’s vast timber reserves. Over the next two years, 80 shipyards in 17 states focused on filling these orders. However, when the war ended in November 1918, of the 300 under construction, only 98 of the ships had been delivered, and not a single one had sailed to a European port. Due to mechanical failures and construction issues, only 76 of those could carry cargo.

While many believed the days of wooden ships were numbered, it was decided that by using wood, ships could be built faster using the U.S.’s vast timber reserves. Over the next two years, 80 shipyards in 17 states focused on filling these orders. However, when the war ended in November 1918, of the 300 under construction, only 98 of the ships had been delivered, and not a single one had sailed to a European port. Due to mechanical failures and construction issues, only 76 of those could carry cargo.

When the war ended, these ships were scuttled in the Potomac River, where they could be salvaged for scrap, especially the metal in the engines, boilers, and propellers. West Marine and Salvage Corporation bought most of the ships and kept them near Mallows Bay, intending to take them a few at a time to Alexandria to break them down into components. However, the process was deemed economically unfeasible, and the ships were abandoned.

When World War II broke out, the ships in the Bay were once again the center of attention. In 1942, the federal government issued a contract to Bethlehem Steel Corporation to recover any remaining metal from the fleet. They worked the site until 1945, transporting materials to a facility near Baltimore.

The fleet lay largely forgotten over time, though a scandal broke out in the 1960s when a company named Idamont, Inc. lobbied to remove the remaining hulls. Under investigation, it was revealed that Idamont was a shell company for the Potomac Electric Power Company, which hoped to  build a power generator on the site.

build a power generator on the site.

It was at this point that the House Committee on Government Operations noticed the ecosystem developing in Mallows Bay. They declared that the removal of the remaining hulls was unnecessary, and the Ghost Fleet remains there today, each ship forming an island.

In addition to over 100 ships from World War I, the graveyard contains vessels from the Civil War and an American Revolution-era long boat. Smaller barges and canoes date back even further.

Efforts are underway to identify and preserve the hulls by conducting detailed surveys and mapping projects linking the exact location and condition of each ship. When completed, this will be a valuable resource for historians and archaeologists.

Ships from the EFC shipbuilding program include:

SS Boone: launched 1919, sold for scrap 1922, named by the wife of Woodrow Wilson

SS Afrania: ran trials in Portland, OR, in 1919, sold for salvage prior to 1926

SS Afrania: ran trials in Portland, OR, in 1919, sold for salvage prior to 1926

Dertona: launched in Portland, OR, in 1918, the best surviving example of hull construction

Moosabee: launched in 1919, used for timber runs until 1922

SS Accomac: wooden steamship launched in 1918

SS Aberdeen: wooden cargo ship, rendered obsolete on completion

SS Aberdeen: wooden steamship launched in 1918, saw limited action before being abandoned

SS Anacostia: wooden steamship designed for wartime but soon labeled impractical for use

The oldest ship is a Revolutionary-era longboat, which represents a captivating historical artifact and predates the rest of the fleet. The youngest is the Accomac, launched in 1928. It served as a car ferry until 1973, when the Bay-Bridge Tunnel opened, connecting Virginia Beach with the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Several barges and long canoes are scattered about, representing the site’s historical diversity.

Today, this artificial wood and metal reef forms a unique habitat for history enthusiasts, bird watchers, scientists, fishermen, and tourists. The Mallows Bay Ghost Fleet is located along the Captain John Smith, Chesapeake National Historic Trail. It is an ideal location for historical research and archaeology, with artifacts dating back 12,000 years.

In 2019, Mallows Bay was designated a National Marine Sanctuary and is now a bird watcher’s paradise and a prime location for bass fishing. On our brief paddle around, we saw the remains of a beaver dam that was destroyed in a storm last winter after surviving there for ten years, Bald Eagle nests, Ospreys feeding their young, and a brown river snake. In a creek off of the burn basin were PawPaw trees, Mountain laurels, Tuckahoe, cattails, and many other native plants. Above and below the water, the fleet’s hulls provide homes for birds, reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates, and mammals in this thriving ecological zone.

In 2019, Mallows Bay was designated a National Marine Sanctuary and is now a bird watcher’s paradise and a prime location for bass fishing. On our brief paddle around, we saw the remains of a beaver dam that was destroyed in a storm last winter after surviving there for ten years, Bald Eagle nests, Ospreys feeding their young, and a brown river snake. In a creek off of the burn basin were PawPaw trees, Mountain laurels, Tuckahoe, cattails, and many other native plants. Above and below the water, the fleet’s hulls provide homes for birds, reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates, and mammals in this thriving ecological zone.