Last month, Dave joked that he missed the book Off 13, which we used for weekend drives while we lived on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Route 13 runs down the spine of the peninsula, and it’s hard to get anywhere without being on part of it. If we had nothing going on, we’d grab the book and explore. We found the most interesting places. We don’t have a book on Southern Maryland, so I joked that we should see how many historical markers we could find in the local counties.

Last month, Dave joked that he missed the book Off 13, which we used for weekend drives while we lived on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Route 13 runs down the spine of the peninsula, and it’s hard to get anywhere without being on part of it. If we had nothing going on, we’d grab the book and explore. We found the most interesting places. We don’t have a book on Southern Maryland, so I joked that we should see how many historical markers we could find in the local counties.

Dave found a couple pertaining to a site on Cobb Island, southeast of us, on a peninsula jutting into the Potomac River. In 1900, Reginald Aubrey Fessenden and Frank W. Very experimented with electromagnetic waves. The men sent and received the first intelligible voice transmission between two 50’ tall masts 100 miles apart. How cool is that?

After a lovely lunch on the island, we started north again, but there were more historical markers to see nearby. I’ll be the first to admit the Civil War era is not one of my favorite periods in history. Blame it on my Midwest upbringing. I hail from the perplexing state of Missouri, whose governor, fist held high in the air, led the charge to secede. However, the other members of the state government did not follow him.

Little did I know we would follow the route of southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth on his 12-day evasion of law enforcement after he killed President Abraham Lincoln in Ford’s Theatre on April 14th, 1865. His well-planned escape route ran down the southern Maryland peninsula.

Who was John Wilkes Booth? He’s been called a villain, an assassin, a traitor, and a murderer. But prior to that fateful day, he was called a charming, charismatic, dashingly good-looking actor. He was born in Bel Air, Maryland, north of Baltimore, to a well-known theatre family. His father, Junius Brutus Booth, was considered to be the greatest actor of the century. Ironically, he was named after the man who assassinated Julius Caesar. John’s older brother, Edwin, was considered the best Shakespearean actor of his day.

John followed in their footsteps, creating quite a stir when the New York Herald raved about his performances, calling him a “veritable sensation” and the “ultimate Richard III.” In response, Booth replied, “I am determined to be a villain.”

No truer words were spoken. Just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Booth joined the Know Nothings, an anti-Catholic hate group/political party that also opposed immigration. This group tended toward violence, burning churches, rioting, and subjecting a Catholic priest to tar-and-feathering. As the war broke out, he sympathized with the South and operated as a secret agent for the Confederacy.

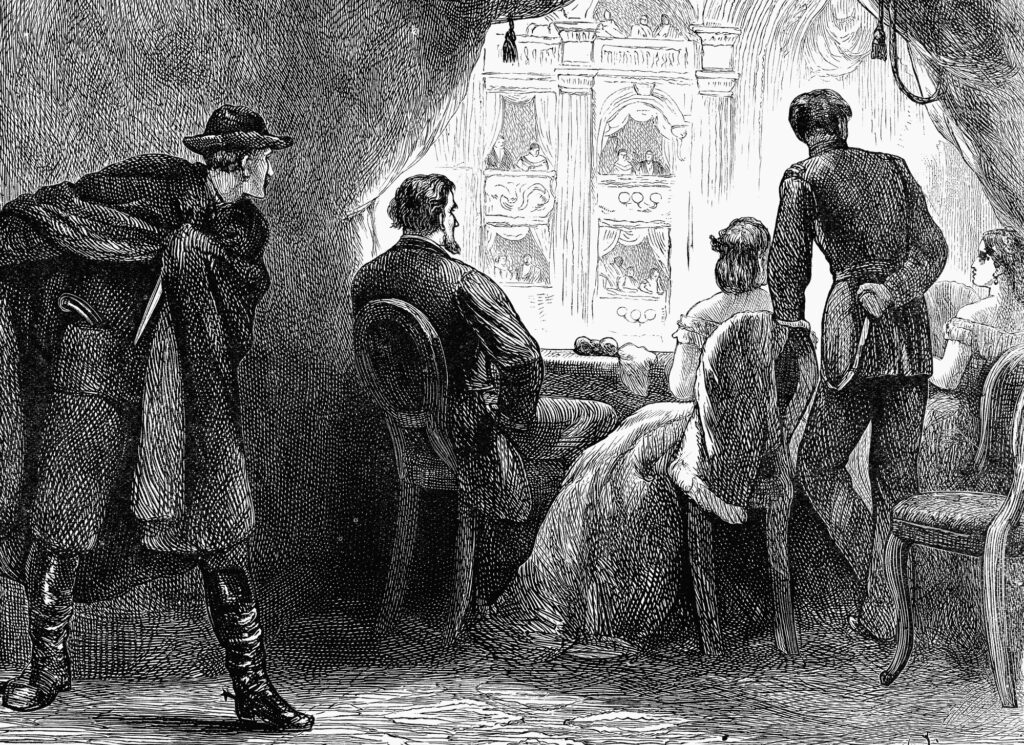

Believing it was his duty to save the country, he saw himself as a heroic instrument for change. He attempted to kidnap President Lincoln so he could ransom him back to the government. However, this plot failed. When Booth learned the President would attend the evening performance of My American Cousin on the 14th, he knew this was his signal to act. He lured his two friends, Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt, to help. Lewis would kill Secretary of State Seward, and George would kill Vice-President Andrew Johnson. Booth kept the main prize for himself. Powell failed in his attempt, and Atzerodt hid in the local pub drinking, unable to summon the courage to act.

John Wilkes Booth, on the other hand, succeeded in his mission. That evening, he hid in a hallway outside the Presidential Box. Unfortunately, Lincoln’s bodyguard went out for a drink. Most historians, however, are of the opinion that it would not have mattered. Booth was such a well-known personality that the famous actor would likely have been invited in to see the President.

Booth forced his way inside, shot Lincoln, and leaped to the stage shouting “sic semper tyrannus,” or “thus always to tyrants,” the Virginia state motto. He broke his leg in the process.

Booth fled Ford’s Theatre into Maryland, where he knew Confederate sympathizers would assist him. He’d planned his escape route meticulously before he acted. A sentry on the Anacostia Bridge stopped Booth. Civilians were not allowed to cross at night, but the smooth actor conned his way through, and the sentry made an exception. Word of the assassination had not spread that far yet. Across the river, he met up with his friend, David Herold, and the two traveled to Surratt Tavern, nine miles away, where they had stashed weapons and ammunition.

acted. A sentry on the Anacostia Bridge stopped Booth. Civilians were not allowed to cross at night, but the smooth actor conned his way through, and the sentry made an exception. Word of the assassination had not spread that far yet. Across the river, he met up with his friend, David Herold, and the two traveled to Surratt Tavern, nine miles away, where they had stashed weapons and ammunition.

Soon, there was a $100,000 bounty placed on his head. By 4:00 AM on the 15th, Booth realized he could go no further with his broken leg, and the pair stopped at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd in Charles County. Later, the doctor testified in court that in the wee hours of the morning, two men arrived at his door, claiming one had fallen from his horse. The good doctor set the leg and gave the men a room for the rest of the night. However, against his sound advice, they slipped out and continued on their way toward Washington, D.C.

For the next five days, Booth and Herold hid in a pine thicket near Zekiah Swamp, where Confederate sympathizer Thomas A Jones brought them food and newspapers. Expecting to find himself hailed a hero, Booth was stunned to find the opposite. His act was labeled treason, and he was referred to as a devil, and a villain, among other names. Not only had the South not risen again due to his heroic act, but church bells in both the North and South rang across the nation in mourning for President Lincoln.

For the next five days, Booth and Herold hid in a pine thicket near Zekiah Swamp, where Confederate sympathizer Thomas A Jones brought them food and newspapers. Expecting to find himself hailed a hero, Booth was stunned to find the opposite. His act was labeled treason, and he was referred to as a devil, and a villain, among other names. Not only had the South not risen again due to his heroic act, but church bells in both the North and South rang across the nation in mourning for President Lincoln.

On the evening of April 21st, local landowner Col. Samuel Cox of Rich Hill and his brother Thomas helped the pair escape to Virginia, which was more friendly to southern sympathizers than Maryland. Later, Herold would testify that in stormy weather and high winds, the pair became confused and ended up paddling their way back into Maryland.

On the 22nd, the pair made a successful crossing to Virginia, landing at the home of Elizabeth Quesenberry, who had aided the Confederate cause during the war. In her testimony, she admits that Herold came to her door seeking help but claims she refused out of fear for her life and that of her family. She testified that she told him to walk away, and though he seemed surprised by her answer, he left.

The following evening, they appeared on the doorstep of the home of Dr. Richard H. Stewart, seeking accommodation. Having heard the news from Washington, he refused them, and the two continued to the home of William Lucas, a free African-American farmer living nearby. When the farmer tried to refuse, he was threatened at knife point. In his testimony, he said he was so afraid that he and his wife spent the night outside on the porch, allowing the men to take over his home.

Booth and Herold made their way deeper into Virginia by any method they could, including by threat at ferry crossings. Finally, twelve days later, the two men were cornered in a tobacco barn on Richard Garrett’s farm. According to the testimony of Sergeant Boston Corbett, they set the barn on fire when the men refused to come out. Once alit, David Herold surrendered and came out. John Wilkes Booth refused. The young sergeant thought Booth was about to shoot him, and in Corbett’s words later, “I took steady aim on my arm and shot him through a large crack in the barn.” The shot entered his neck, and Booth was dead by 7:00 in the morning.

There have been suggestions that it was not Booth in the barn that day and that he had escaped. However, testimony from those who knew him certified it was John Wilkes Booth who was killed that morning twelve days after murdering President Lincoln.

We followed the trail on the Maryland side through the pine thicket beside the swamp and found Cox’s Rich Hill home along with the spot where they hid out in Zekiah Swamp. You just can’t make this stuff up!