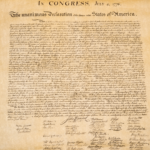

Everyone’s heard the phrase, “Put your John Hancock on it.” Did you ever wonder where the phrase came from? John Hancock was one of the fifty-six delegates to the Continental Congress to sign the Declaration of Independence. In fact, Hancock was the first man to sign it, and he did so with a large, bold hand. He claimed he did that so that King George would be able to read it without his glasses. So, putting your John Hancock on a document came to mean signing your name on something.

Everyone’s heard the phrase, “Put your John Hancock on it.” Did you ever wonder where the phrase came from? John Hancock was one of the fifty-six delegates to the Continental Congress to sign the Declaration of Independence. In fact, Hancock was the first man to sign it, and he did so with a large, bold hand. He claimed he did that so that King George would be able to read it without his glasses. So, putting your John Hancock on a document came to mean signing your name on something.

Just down the road from us is the home of Thomas Stone, one of the four Maryland delegates to sign the Declaration of Independence. I admit that, like most Americans, I can name only a few of those fifty-six men, much less who the four from Maryland were. So after we explored the property, I came home and googled it. In addition to Thomas Stone, the other three who signed the document were William Paca, Samuel Chase, and Charles Carroll (the only Catholic to sign), all of Anne Arundel County.

I know Thomas Jefferson is credited for writing it, and the first draft may have been his, but a committee of five penned the declaration. Today, it seems only the names of the more vocal members come to mind, men like Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, and John and Samuel Adams, to name a few. Many will name George Washington or Patrick Henry, neither of whom signed it. Nor did Alexander Hamilton, who, at the age of 19, was with General Washington defending New York. But what about the other men, those who were considered moderate in their views? These men are often forgotten. Thomas Stone was one of them.

Can you imagine standing up for your beliefs even though you may lose your property, possessions, or even your life? That was the decision these men had to make, and it was not an easy choice for any of them. In a debate on 24 April 1776, Thomas Stone said, “You know my heart wishes for peace upon terms of security and justice to America. But war, anything, is preferable to a surrender of our rights.”

Can you imagine standing up for your beliefs even though you may lose your property, possessions, or even your life? That was the decision these men had to make, and it was not an easy choice for any of them. In a debate on 24 April 1776, Thomas Stone said, “You know my heart wishes for peace upon terms of security and justice to America. But war, anything, is preferable to a surrender of our rights.”

For those who had been loyal British subjects, the transition to being a revolutionary was a slow, deliberate process and one not lightly taken. Stone, ever cautious, is considered one of the reluctant revolutionaries, along with John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and others. However, once Stone made the decision, he supported it wholeheartedly.

Thomas Stone was born in 1743 at Poynton Manor, Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland. Not much is known about his early years, though he studied Greek, Latin, and philosophy before his instruction in the law. After he finished his legal education in 1765, he practiced law as a circuit rider stretching from Port Tobacco to Annapolis. He was known as a man of caution who weighed each decision carefully.

In 1768, Thomas married Margaret Brown, the daughter of a prominent physician. Two years later, he purchased the 442-acre plantation known as Haberdeventure from his uncle, Daniel Jenifer. While Stone came from a prominent family, his great-grandfather had served as the Governor of Maryland, his wife, Margaret’s, fortune was far greater than his. Much of her dowry was used to buy the property. By his death in 1787, he had expanded the estate to over 2,000 acres, including one of the most active grist mills in the area.

Stone was chosen to become a member of the Charles County Committee of Correspondence at the age of thirty-one, beginning his political career. The Committees were critical communication networks between the colonies, stretching from Georgia to Nova Scotia. The goals were to establish a method of communication between the assemblies of each of the colonies and rally support for the cause of American independence.

The following year, the small-town lawyer was chosen to represent Maryland at the Second Continental Congress. Fighting had already begun in Lexington and Concord by the time the Congress met in May 1775. They were three weeks too late.

The following year, the small-town lawyer was chosen to represent Maryland at the Second Continental Congress. Fighting had already begun in Lexington and Concord by the time the Congress met in May 1775. They were three weeks too late.

Thomas Stone was a peace lover and believed a peaceful resolution could still be achieved even after Bunker Hill. He was one of the Congressmen urging a letter to be sent to King George III. Known as the Olive Branch, the king refused to read it. He considered the colonies to be in rebellion to his authority.

By the time the Congress met again in May 1776, the majority of delegates favored independence. On 7 June, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee declared, “… these united colonies are, and of right, ought to be, free and independent states, absolved of any and all allegiance with Great Britain.” After this, Jefferson and his committee met to draft the document. The proposition was completed and, on 2 July 1776, was approved by 12 of the 13 colonies. New York would eventually sign on 15 July. Thomas Stone and most of the other fifty-five men signed on 2 August.

Stone served out his term but declined reappointment in 1777. His decision to accept a position with the Maryland State Senate was primarily based on his wife’s illness. Margaret was bedridden for most of the final years of her life, and he wished to remain close to her.

The property is spelled in various ways in historical documents, including Habre de Venture. But by any spelling, the name seems to come from the Latin “havitatio de ventus,” meaning to dwell in the wind. And the day we visited, along with a light rain, it was quite windy.

Due to his wife’s declining health, Thomas purchased a home in Annapolis in 1783, and the family moved into the residence there by 1784. Margaret died in 1787, and her husband followed her four months later. Both are laid to rest on the property at Haberdeventure.

Despite the misty rain, it was a lovely walk, and we learned so much about a typical American revolutionary who was forced to make a tough decision. If you were in their position, what would you decide?

Carol,

Another great article. They are always so informative and enlightening. Thanks, keep up the great work.

Thanks so much. I’m having such fun with them.